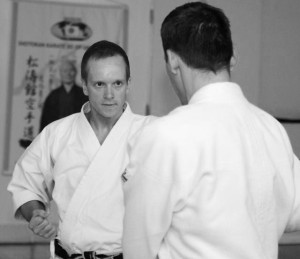

The gentleman in the picture at the top of this article is Adrian Miles. Adrian is a nidan (he’ll be sandan soon, if there’s any justice), and has been part of a world championship winning kata team. He’s far from a slouch at kumite, either.

The gentleman in the picture at the top of this article is Adrian Miles. Adrian is a nidan (he’ll be sandan soon, if there’s any justice), and has been part of a world championship winning kata team. He’s far from a slouch at kumite, either.

Adrian and I have trained together for a goodly chunk of twenty years. It so happened that a little while ago we both had personal issues that kept us from the dojo for a while, and by the time we both made it back, there were people training at our club who had never seen either of us before.

I got back to training a little before Adrian, and got to know a few of them, and a little while afterwards, Adrian returned as well.

After the first training session in which Adrian and I sparred, one of the newer students sidled up to me and asked ‘Pete, have you and Adrian got a bad history with each other?’

I was more than a bit surprised by this.

‘No!’ I replied. ‘Adrian is my buddy, my brother. We’ve been training together for years…what makes you say that?’

‘Well, you fight like you’re sincerely trying to do each other an injury…I just thought there might be some bad blood!’

This brought me up a little short. It’s true that when Adrian and I spar we go at it hammer and tongs…but actual hostility? Never. We practice kumite with total commitment and total control; strong spirit doesn’t mean anger or hatred.

For a start, fighting angry is a mistake, in any circumstance.

It’s a folk truism that ‘venting,’ engaging in vigorous aggressive sports, or attacking a punch bag or pillow diminishes anger and hostile impulses. It turns out that, in fact the opposite is true; when you are angry expressing your anger through physical aggression feels really good, and so normalises violence as a response to feeling angry.

College students (the go to guinea pigs for psychologists) were asked to complete a simple essay, and then it was returned with an unnecessarily harsh mark, and negative comments scrawled on it in red pen.

Understandably they felt aggrieved, and half were offered the suggestion that they punch couch cushions for two minutes, and others were told to sit and relax and calm down by breathing and relaxing.

A short time after that, all of them were given a plastic cup, and a bottle of Tabasco sauce and asked to pour into the cup the amount of hot sauce they wanted the person who had marked their essay to drink. The group who had punched cushions filled the cups higher.

Anger is high in the list of ‘Top Ten Emotional States Likely to Cause a Mistake or Bad Decision.’ Powerful emotion short circuits the ability to make rational, considered decisions. Anger and it’s kissing cousin fear are especially powerful at robbing the human brain of sense. This is not necessarily a bad thing; like everything else the human body does it happens because doing so promotes surviving to reproduce.

On the plains of Africa, our ancestors were divided, when confronted by a predator or other danger, between those who just ran for it, and those who thought carefully about what to do. The first group had children, the second group became lunch, and the tendency to instinctively flee danger became further ingrained in the species.

When denied a route of escape, fear becomes anger and we go for the ‘fight’ of ‘fight or flight,’ and the sabre toothed tiger has a struggle for its meal, perhaps enough of a struggle to make it a safer bet to let this one go and find something weaker.

Well, the Smilodons are gone now (I’m not even sure they were contemporary with humans…pre-history cliché #268), but we are still, basically, the same creatures who crept fearfully around the Serengeti a hundred thousand years ago. Our biological evolution has not kept pace with our technological and societal development., and the same powerful emotional reactions can now cause us problems.

Things still make us afraid, and make us angry, even things which can’t really hurt us, and the instinctive reaction within the brain overrides logical thought. An arachnophobe can acknowledge, logically, that most spiders cannot hurt them; when confronted with one, however, the flood of hormones from the amygdala, the primitive hind brain area that drives the fear response, washes away that logical consideration and demands only flight.

There are no wrong feelings; being angry is not wrong, being afraid is not wrong. We cannot control how we feel; but we can with understanding and effort, control the way we act. If we don’t learn to control our actions, we risk making mistakes.

If we cannot control our actions in response to fear, we may become a prisoner to it, avoiding situations, people and objects, limiting our lives; if we cannot control our actions in response to anger, we risk hurting others and ourselves, psychologically and physically.

It might seem that anger would be of benefit to learning a fighting art, but this is not the case. A principal rule of learning budo karate is that it is not for use willy-nilly, to enforce our will upon others.

To train with a feeling of anger would psychologically tie anger to karate…and the next time something makes you angry, you may respond with karate. This is definitely not ok. In addition, the people we train with are not our enemies; but if you spar angry they may become so.

To be sure, one should practice kumite with commitment and even aggression; but aggression is not anger.

Most people have some idea of how a court of law operates. In court, some of the most difficult and upsetting issues arising from human society are discussed, usually in the form of an argument about who is in the right and who is in the wrong. The process is so complex that in most cases it is necessary to employ a representative to carry on the case on your behalf.

Solicitors (attorneys, if this gets as far as the US) are trained to negotiate the procedure and fight their client’s corner, with total commitment and even a good deal of aggression; they usually get more pay if they win. But these people see each other every day, and are even friends professionally and personally. How can you lace into a friend for all you are worth and remain friends?

The answer is manners. Manners are the social conventions that grew up to curb the worst excesses of anger and fear.

In a courtroom, etiquette is everything. The judge is accorded a high degree of respect, addressed formally and politely by all involved, even to the point of standing when he enters and leaves.

In higher courts, Judge and Barristers wear strange archaic robes, and in all courts formal modes of address and speaking are observed. Failure to adhere to these rules carries strict punishments, up to and including jail time.

The effect of this, at first bizarre, mode of behaviour is that it enables all concerned to carry out their job, which is basically having a contentious argument, to the best of their ability in such a way that it does not become actively hostile.

Under these rules, it is perfectly possible for a solicitor to prosecute his case with a high degree of aggression, but no anger, and thus be able to look his opponent in the eye as a friend and colleague later in the lounge bar of the Chamber Tap.

The manners and etiquette of traditional karate perform the same function.

We wear clothes that we only wear while training. We address each other in ways we only use while training. We perform gestures of respect and friendliness with regularity and sincerity. These behaviours continually reinforce in our minds that this is training, that we are all friends, brothers even, and owe each other loyalty and trust.

As these cues become stronger, it becomes possible to increase the pace, commitment and aggression of sparring in an atmosphere of total trust and a complete lack of anger, fear and hostility. This helps ensure that in the event we end up facing aggressive behaviours fuelled by hostile emotions, we are not discombobulated by their intensity, and negatively affected by fear.

Further, the forms of etiquette – bowing, formal modes of address – promote the perfection of character sought by budo karateka. Addressing your seniors as sempai and sensei, bowing first and bowing lower, listening attentively and replying ‘Osu!’ with spirit are not meant to feed the ego of the senior grade…they are meant to diminish your own.

So, when Adrian and I face each other for kumite, staring impassively into one another’s eyes, we know that we can trust each other to fight to the best of our ability without regard for petty considerations like winning and losing. Development is all that counts, and it is diligent, correct etiquette that allows us to train this way, such good friends that those who watch us spar may think we are enemies.

Forgot to mention: Thanks to Steve Wadlan for the use of the photo.

Brilliant explanation.Beautifully written.Pete just changed my life

Thanks, dad :p